Dating Violence Among College Students In Usa

Researchers have identified the correlation between risky health and behavioral factors and dating violence, most often modeling these as part of the etiology of dating violence among college students. Less often have scholars explored these as co-occurring risk factors. The domestic violence field is learning new things all the time. One area that’s increased in awareness is dating violence, especially among high school and college students. February has been designated as Teen Dating Violence Awareness Month to help boost that effort. So, how serious is dating violence for high schoolers? Teen dating violence has serious consequences for victims and their schools. Witnessing violence has been associated with decreased school attendance and academic performance. Vi 20% of students with mostly D and F grades have engaged in dating violence in the last year, while only 6% of students with mostly A’s have engaged in dating.

College dating is the set of behaviors and phenomena centered on the seeking out and the maintenance of romantic relationships in a university setting. It has unique properties that only occur, or occur most frequently, in a campus setting. Such phenomena as hooking up and lavaliering are widely prominent among university and college students. Hooking up is a worldwide phenomenon that involves two individuals having a sexual encounter without interest in commitment. Lavaliering is a 'pre-engagement' engagement that is a tradition in the Greek life of college campuses. Since fraternities and sororities do not occur much outside of the United States, this occurs, for the most part, only in the US. Technology allows college students to take part in unique ways of finding more partners through social networking. Sites such as Facebook, Twitter, and MySpace allow students to make new friends, and potentially find their spouse.

Date rape, violence, and sexual harassment also occur on college and university campuses. Victims of abuse come from every race and gender. Another potential form of harassment can be seen in professor–student relationships; even though the student may be of the age to consent, they might be coerced into sexual encounters due to the hope of boosting their grades or receiving a recommendation from the professor.

History[edit]

The practices of courtship in Western societies have changed dramatically in recent history. As late as the 1920s, it was considered unorthodox for a young couple to meet without familial supervision in a tightly controlled structure. Compared with the possibilities offered by modern communications technology and the relative freedom of young adults, today's dating scene is vastly different.[1][2]

The primary change in courtship rituals during this time was a shift from marriage to social status as the desired result. Before the 1920s, the primary reason for courting someone was to begin the path to marriage. It functioned as a way for each party's family to gauge the social status of the other. This was done in order to ensure a financially and socially compatible marriage. This form of courtship consisted of highly rigid rituals, including parlor visits and limited excursions. These meetings were all strictly surveyed, typically by the woman's family, in order to protect the reputations of all involved and limit such possibilities as pregnancy. This manner of courtship system was mostly used by the upper and middle classes from the eighteenth century through the Victorian period. The lower classes typically did not follow this system, focusing more on public meetings. However, the goal of the process was still focused on ending in a marriage.[1][2]

Around the 1920s, the landscape of courtship began to shift in favor of less formal, non-marriage focused rituals. The date, which had previously been the public courting method for the lower class, was adopted by young adults across the upper and middle classes. Meetings between lovers began to be more distant from rigid parental supervision. A young man might take a girl to a drive-in movie rather than spend an evening in the parlor with her family. While no two accounts of dating history completely agree on the timeline for this change, most do agree that new technologies were linked to its cause. Specifically, the advent of the telephone and the automobile and their subsequent integration into the mainstream culture are often identified as key factors in the rise of modern dating. Not only did these technologies allow for rapid communication between a couple, but they also removed familial supervision from the dating process. The automobile especially afforded a young couple the opportunity to have time together away from parental constraints.[2]

With the shift of courtship from the private to the public sphere, it took on a new goal; dating became a means to and indicator of popularity, especially in the collegiate environment. In this format, dating became about competing for the potential mate with the highest social payoff. On a campus in the late 1930s, a man's possession of a car or membership in a key fraternity might win him the attention of his female classmates. Women's status was more closely tied to how others perceived them. If they were seen with the right men and viewed as someone who was desired and dateable, they would achieve the desired social status.[1][3]

Hooking up[edit]

It is common for college students to seek sexual encounters without the goal of establishing a long-term relationship, a practice commonly referred to as hooking up.[4] Hooking up can have different meanings to different college students. For instance, at Howard University, the majority of students see hooking up as meeting friends or simply exchanging phone numbers without any sexual connotation to it.[5] Hooking up is unique for when and why the sexual encounter occurs: instead of building a relationship before initiating sexual acts (from kissing to intercourse), hooking up allows the participants to become intimate without the expectation of commitment.[6]

Glenn and Marquardt's research shows the prominence of hooking up on modern-day college campuses; they found that approximately 40% of college women have participated in a hookup, with as many as 25% of that number having participated in this practice a minimum of six times.[4] A majority of hookups occur when the participants have been drinking.[7] It is often used to remove inhibitions and allow participants to use drunkenness as an excuse for a not commonly accepted behavior in society.[8] It allows women to be more sexual than if they were sober, and can be the cause of the sudden increase in drinking at parties among teens recently.[6]

In countries other than the United States, other terms are associated with hooking up such as casual sex and short-term mating.[9] A research study performed by Todd Shackelford, showed that short-term mating occurs in all 46 of the nations that he researched. It occurred least frequently in Poland, Ethiopia, and Congo; and it occurred most frequently in Lithuania, Croatia, and Italy.[10]

Lavaliering[edit]

Lavaliering is a common practice among fraternity brothers and their girlfriends within the United States.[11] When a brother decides that he wants to make his relationship more serious, he performs a secretive ritual with his brothers. The term lavalier originates from the name of the mistress, Louise de La Vallière, to the French king, Louis XIV.[12]

Lavaliering is a secretive ritual between the fraternity and the brother's girlfriend. The brother gives his girlfriend his letters or fraternity's insignia in order to label her as becoming a sexual possession to him.[13] One young woman explains, 'Several brothers came to my dorm room and blindfolded me. ... My blindfold was eventually removed, and I could see the room was filled with brothers all wearing their robes used for fraternity rituals. The only light was from lit candles around the room. At first I was a bit nervous, but then I saw my boyfriend and knew that everything was going to be alright.'[14] Usually, after the ceremony is completed, the fraternity brother is berated for showing his loyalty to his girlfriend instead of the fraternity house. According to one account, the brother is tied to a bed post in the house, and 'someone pours beer down his throat until he vomits. After he vomits, the girlfriend is supposed to kiss him.'[15]

Technology[edit]

College dating, like many other forms of relationships, is being influenced by the application of new technologies. The most prominent among these technological advances is the rise in popularity of social networking and matchmaking sites such as DateMySchool, a website dedicated to college dating (established in 2010). These new technologies modify certain aspects of the current system of relationship formation, rather than fundamentally changing it. Participants in these services who are looking for a face-to-face relationship still tend to impose geographical and group-based limitations on the pool of potential mates. This indicates that, despite the increased number of possibilities, users still value the possibility of an offline relationship. Participants use the services in order to meet others who are outside their social circles, but still attempt to impose some limitations to maintain the possibility of a physical relationship.[16][17]

While the current literature on the specific effects of the advent of the internet on university-age dating is somewhat lacking and contradictory, there is agreement that it follows the trends of the general population. When students use the internet to find and create relationships, the most common bonds formed are on the level of friends and acquaintances. About ten percent of those interviewed reported one or more romantic relationships that had originated online.[17]

One prominent trend in this literature is the assertion that those with social/dating anxiety disorders are more likely to use online media to initiate relationships than those without those disorders.[2][17] However, when this proposition was recently explicitly tested by Stevens and Morris, they found that the difference was not in the type of relationship sought, but in the methods used to seek it. They found that there is no significant difference in between those ranking high and low in risk for social or dating anxiety in the types of relationships that are formed through the internet. The difference lies in the fact that those with high anxiety indexes used webcams to communicate with people they had met and maintain their relationships. Stevens and Morris speculated that webcams allow for some of the benefits of face-to-face communication while retaining some of the buffering effects of cyber-communication, alleviating the social anxiety of the user.[17]

Date rape, sexual violence, and harassment[edit]

Dating violence occurs in both heterosexual and homosexual relationships, and is defined as verbal, physical, psychological or sexual abuse to either gender.[18] Approximately 35% of college students have been subjected to dating violence in a relationship, and the victims are often faced with self-blame, embarrassment, and fear of their perpetrator.[18][19]

Date rape is a common problem on college campuses; between 15 and 25 percent of college women experience date rape, and over fifty percent of college-aged men were sexually aggressive while on a first date.[20][21][22][23]Date rape is most likely to occur in a student's first ten weeks of school, when they are more likely to trust others and may be engaging in social encounters outside of the mediating influence of their parents.[22]Alcohol consumption has also been identified as a strong predictor of a woman's likelihood of being date raped at college.[24][25] Alcohol consumption and sexual assault has been prevalent during fraternity parties, where victims are placed under social control and fear retaliation for speaking up against sexual violence. [26]

Sexual violence on campus can take on different forms. Physical abuse includes all forms of intending harm onto others: psychological, physical, and emotional.[18] Sexual violence, however, only includes forcing oneself sexually onto another individual without consent, and encompasses both abuse and harassment.[18] Both physical and sexual abuse on college campuses are becoming widespread problems that are on the rise.[18] 33% of women have been physically or sexually abused by their partners before they turn eighteen, and 40% of individuals know someone who has been physically abused; the rates do not differ between heterosexual and homosexual relationships.[27]

Sexual harassment on campus can occur from authority figures, such as faculty members, or from the victim's peers in the college setting. Regardless as to where the abuse comes from, the end-effect usually leaves the victim feeling used.[28]Harassment can occur from and towards either gender; however, males may face a second form of harassment when disclosing what has happened to them because they are going against cultural norms by reporting the attack.[28] In an international study, including thirty-one countries, more women than men (twenty-four percent versus thirteen percent) had become physically abusive to their partner in the past year.[29] When an authority figure harasses a student, the attacks are usually more severe than when another peer harasses a student, and over two-thirds of these attacks are targeted more at girls.[28] Sexual harassment has not decreased, but thankfully 40% more victims are coming forward to report their cases.[28]

Since 1992, federal law in the U.S. has required that institutions of higher learning keep and report statistics on sexual assaults on campus. Colleges have also started education programs aimed at reducing the incidence of date and acquaintance rape. One priority is getting victims to report sexual assaults, since they are less likely to report one if it is an acquaintance.[22]

Professor-student relationships[edit]

The phenomenon of student-teacher romantic and sexual relationships is one that is found across many types of school systems, age groups, and demographics.[30][31][32] However, in the collegiate setting, this phenomenon must be viewed differently. While the consequences and social problems of these relationships are relatively clear in elementary and secondary settings, the issue becomes more complicated in a university. The fact that the vast majority of college students are at or above the age of consent means that romantic relationships between faculty and students are not necessarily illegal. This differentiates the issue from concerns over such relationships in elementary and secondary schools.[33]

The main concern about teacher-student romance in the university setting is largely one of potential conflicts of interest. If a student and a professor are in a relationship while the student is enrolled in that professor's class, there is the possibility that their relationship could create conflicts of interest. Besides the potential breach of classroom etiquette, there is also concern over grading impartiality. Another possible issue that since professors have so much power over their students (in matters of grading, recommendations, etc.), it is uncertain if the consent to sex by the student is valid and un-coerced.[31][33]

References[edit]

- ^ abcBailey, Beth L. From Front Porch to Back Seat. Johns Hopkins University Press. 25-56.

- ^ abcdLawson, Helene M. and Kira Leck (2006). 'Dynamics of Internet Dating'. Social Science Computer Review. 24: 189.

- ^Waller, Willard. 'The Rating and Dating Complex'. American Sociological Review. 2.5: 727-734.

- ^ abAmericanvalues.orgArchived 2011-10-18 at the Wayback Machine, Glenn, Norval & Marquardt, Elizabeth 'Hooking Up, Hanging Out, and Hoping for Mr. Right: College Women on Dating and Mating Today' pg 13.

- ^americanvalues.orgArchived 2011-10-18 at the Wayback Machine, Hooking Up, Hanging Out, and Hoping for Mr. Right: College Women on Dating and Mating Today, Glenn, Norval, Marquardt, Elizabeth, pg 14.

- ^ abKathleen A. Bogle (2008). Hooking up: sex, dating, and relationships on campus. NYU Press. pp. 47–. ISBN978-0-8147-9969-7. Retrieved 2 November 2011.

- ^americanvalues.orgArchived 2011-10-18 at the Wayback Machine Hooking Up, Hanging Out, and Hoping for Mr. Right: College Women on Dating and Mating Today, Glenn, Norval, Marquardt, Elizabeth, pg 15.

- ^americanvalues.orgArchived 2011-10-18 at the Wayback Machine Hooking Up, Hanging Out, and Hoping for Mr. Right: College Women on Dating and Mating Today, Glenn, Norval, Marquardt, Elizabeth, pg 16.

- ^www.epjournal.net Big Five Traits Related to Short-Term Mating: From Personality to Promiscuity across 46 Nations, Shackelford, Todd, pg. 246.

- ^www.epjournal.net Big Five Traits Related to Short-Term Mating: From Personality to Promiscuity across 46 Nations, Shackelford, Todd, pg. 270.

- ^Nicholas L. Syrett (28 February 2009). The company he keeps: a history of white college fraternities. UNC Press Books. p. 13. ISBN978-0-8078-5931-5. Retrieved 17 November 2011.

- ^Tixall letters (1815). Tixall letters; or The correspondence of the Aston family, and their friends, during the seventeenth century, with notes by A. Clifford. pp. 119–. Retrieved 2 November 2011.

- ^Lynn H. Turner; Helen M. Sterk (November 1994). Differences that make a difference: examining the assumptions in gender research. Bergin & Garvey. p. 131. ISBN978-0-89789-387-9. Retrieved 14 November 2011.

- ^Shaun R. Harper; Frank Harris, III (8 March 2010). College men and masculinities: theory, research, and implications for practice. John Wiley and Sons. pp. 268–. ISBN978-0-470-44842-7. Retrieved 14 November 2011.

- ^Brandy Taylor Fink (August 2010). Disrupting Fraternity Culture: Folklore and the Construction of Violence Against Women. Universal-Publishers. pp. 33–. ISBN978-1-59942-353-1. Retrieved 2 November 2011.

- ^Barraket, Jo and Millsom S. Henry-Waring (2008). 'Getting it on(line): Sociological perspectives on e-dating'. Journal of Sociology. 44: 149.

- ^ abcdStevens, Sarah B. and Tracy L. Morris (2007). 'College Dating and Social Anxiety: Using the internet as a means of connecting to others'. Cyberpsychology and Behavior. 10.5: 680.

- ^ abcdeLaura Finley (30 September 2011). Encyclopedia of School Crime and Violence. ABC-CLIO. pp. 128–. ISBN978-0-313-36238-5. Retrieved 2 November 2011.

- ^Michele Antoinette Paludi (2010). Feminism and women's rights worldwide. ABC-CLIO. p. 96. ISBN978-0-313-37596-5. Retrieved 14 November 2011.

- ^Koss, M. P., Gidycz, C. A., & Wisniewski, N. (1987). 'The scope of rape: Incidence and prevalence of sexual aggression in a national sample of higher education students'. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology55: 162–170.

- ^Ward, S. K., Chapman, K., Cohn, E., White, S., & Williams, K. (1991). 'Acquaintance rape and the college social scene'. Family Relations40: 65–71.

- ^ abcLombardi, Kate Stone (October 25, 1992). 'New Policy Is Aimed at Preventing Date Rape on Campuses'. The New York Times. Retrieved October 24, 2011.

- ^Romeo, Felicia F. 'Acquaintance Rape on College and University Campuses'. College Student Journal (March, 2004). Retrieved October 24, 2011.

- ^Abbey, Antonia (1991). 'Acquaintance Rape and Alcohol Consumption on College Campuses: How Are They Linked?' Journal of American College Health39(4): 165–169.

- ^Kusserow, Richard P. (1992). Youth and Alcohol: Dangerous and Deadly Consequences. Washington DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

- ^Bennett, Jessica. 'Fraternity Misogyny Goes on Long After Graduation'. Time. Retrieved 2016-05-04.

- ^Leighton C. Whitaker; Jeffrey W. Pollard (1993). Campus violence: kinds, causes, and cures. Psychology Press. p. 2. ISBN978-1-56024-568-1. Retrieved 14 November 2011.

- ^ abcdJoseph E. Zins; Maurice J. Elias; Charles A. Maher (2007). Bullying, victimization, and peer harassment: a handbook of prevention and intervention. Psychology Press. pp. 288–. ISBN978-0-7890-2219-6. Retrieved 2 November 2011.

- ^James M. Honeycutt; Suzette P. Bryan (20 August 2010). Scripts and Communication for Relationships. Peter Lang. pp. 355–. ISBN978-1-4331-1052-8. Retrieved 3 November 2011.

- ^Sawyer, Thomas H. 'Teacher-Student Sexual Harassment'. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation, and Dance. 72.5: 10.

- ^ abMardsen, Harry. 'Sex with Students: How some get away with it'. New York Times Educational Supplement. June 25, 2004.

- ^'New York Teacher-Student Sex Crimes on the Rise'. New York Times. June 20, 2007.

- ^ abAlston, Kal. 'Hands off Consensual Sex'. Academe. 84.5:32-33

Teen dating violence (TDV), also called, “dating violence”, is an adverse childhood experience that affects millions of young people in the United States. Dating violence can take place in person, online, or through technology. It is a type of intimate partner violence that can include the following types of behavior:

- Physical violence is when a person hurts or tries to hurt a partner by hitting, kicking, or using another type of physical force.

- Sexual violence is forcing or attempting to force a partner to take part in a sex act and or sexual touching when the partner does not or cannot consent. It also includes non-physical sexual behaviors like posting or sharing sexual pictures of a partner without their consent or sexting someone without their consent.

- Psychological aggression is the use of verbal and non-verbal communication with the intent to harm a partner mentally or emotionally and/or exert control over a partner.

- Stalking is a pattern of repeated, unwanted attention and contact by a partner that causes fear or concern for one’s own safety or the safety of someone close to the victim.

Teen dating violence has profound impact on lifelong health, opportunity, and well-being. Unhealthy relationships can start early and last a lifetime. The good news is violence is preventable and we can all help young people grow up violence-free.

Teens often think some behaviors, like teasing and name-calling, are a “normal” part of a relationship, but these behaviors can become abusive and develop into serious forms of violence. Many teens do not report unhealthy behaviors because they are afraid to tell family and friends.

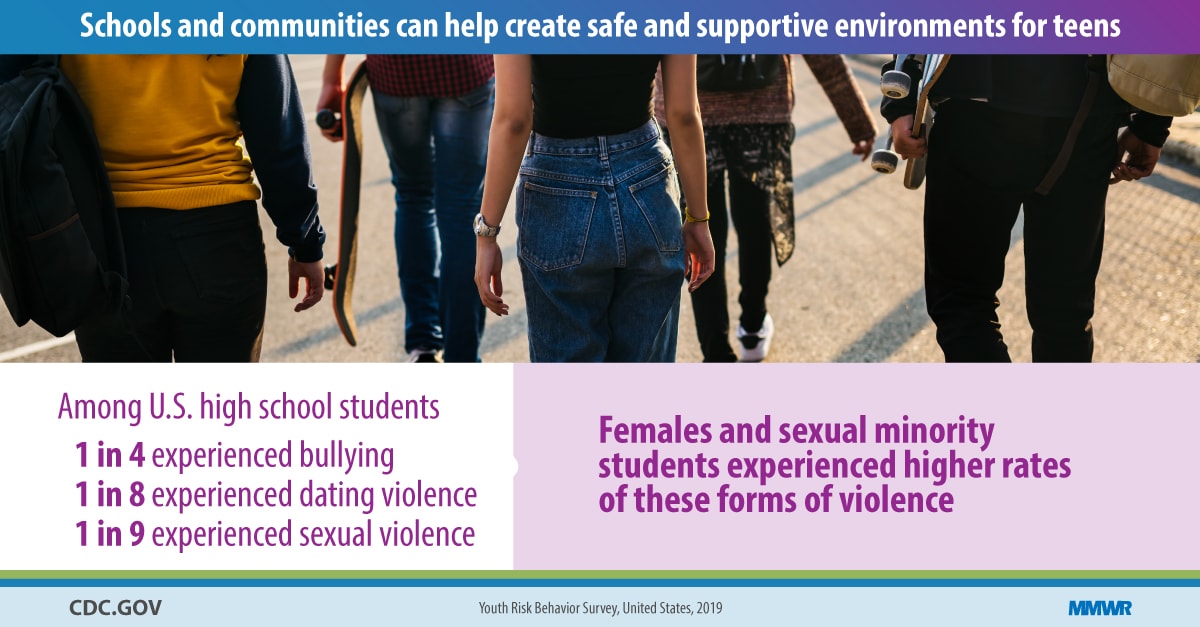

Teen dating violence is common. Data from CDC’s Youth Risk Behavior Survey and the National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey indicate that:

- Nearly 1 in 11 female and approximately 1 in 14 male high school students report having experienced physical dating violence in the last year.

- About 1 in 8 female and 1 in 26 male high school students report having experienced sexual dating violence in the last year.

- 26% of women and 15% of men who were victims of contact sexual violence, physical violence, and/or stalking by an intimate partner in their lifetime first experienced these or other forms of violence by that partner before age 18.

Some teens are at greater risk than others. Sexual minority groups are disproportionately affected by all forms of violence, and some racial/ethnic minority groups are disproportionately affected by many types of violence.

Unhealthy, abusive, or violent relationships can have short-and long-term negative effects, including severe consequences, on a developing teen. For example, youth who are victims of teen dating violence are more likely to:

- Experience symptoms of depression and anxiety

- Engage in unhealthy behaviors, like using tobacco, drugs, and alcohol

- Exhibit antisocial behaviors, like lying, theft, bullying, or hitting

- Think about suicide

Violence in an adolescent relationship sets the stage for problems in future relationships, including intimate partner violence and sexual violence perpetration and/or victimization throughout life. For example, youth who are victims of dating violence in high school are at higher risk for victimization during college.

Supporting the development of healthy, respectful, and nonviolent relationships has the potential to reduce the occurrence of TDV and prevent its harmful and long-lasting effects on individuals, their families, and the communities where they live. During the pre-teen and teen years, it is critical for youth to begin learning the skills

needed to create and maintain healthy relationships. These skills include knowing how to manage feelings and how to communicate in a healthy way.

CDC developed Dating Matters®: Strategies to Promote Healthy Teen Relationships to stop teen dating violence before it starts. It focuses on 11-14-year-olds and includes multiple prevention components for individuals, peers, families, schools, and neighborhoods. All of the components work together to reinforce healthy relationship messages and reduce behaviors that increase the risk of dating violence. Please visit the Dating Matters website to learn more!

CDC also developed a resource, Preventing Intimate Partner Violence Across the Lifespan: A Technical Package of Programs, Policies, and Practices pdf icon[4.52 MB, 64 Pages, 508] that describes strategies and approaches that are based on the best available evidence for preventing intimate partner violence, including teen dating violence. The resource includes multiple strategies that can be used in combination to stop intimate partner violence and teen dating violence before it starts.

Dating Violence Among College Students In Usa Statistics

See Intimate Partner Violence Resources for articles, publications, data sources, and prevention resources for Teen Dating Violence.

Dating Violence Among College Students In Usa Statistics

- Breiding MJ, Basile KC, Smith SG, Black MC, Mahendra RR. (2015). Intimate partner violence surveillance: uniform definitions and recommended data elements, version 2.0. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- Basile KC, Clayton HB, DeGue S, Gilford JW, Vagi KJ, Suarez NA, … & Lowry R. (2020). Interpersonal Violence Victimization Among High School Students—Youth Risk Behavior Survey, United States, 2019. MMWR supplements, 69(1), 28.

- Smith, SG, Zhang, X, Basile, KC, Merrick, MT, Wang, J, Kresnow, M, Chen, J. (2018). The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS): 2015 Data Brief—Updated Release. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

- Foshee VA, McNaughton Reyes HL, Gottfredson NC, Chang LY, Ennett ST. (2013). A longitudinal examination of psychological, behavioral, academic, and relationship consequences of dating abuse victimization among a primarily rural sample of adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health; 53(6):723-729.

- Roberts TA, Klein JD, Fisher S. (2003). Longitudinal effect of intimate partner abuse on high-risk behavior among adolescents. Archives of Pediatric Adolescent Medicine; 157(9):875-881.

- Exner-Cortens D, Eckenrode J, Rothman E. (2003). Longitudinal associations between teen dating violence victimization and adverse health outcomes. Pediatrics; 131(1):71-78.

- Smith PH, White JW, Holland LJ. (2003). A longitudinal perspective on dating violence among adolescent and college-age women. American Journal of Public Health; 93(7):1104–1109.

- Niolon PH, Kearns M, Dills J, Rambo K, Irving S, Armstead T, Gilbert L. (2017). Preventing Intimate Partner Violence Across the Lifespan: A Technical Package of Programs, Policies and Practices. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.